For nearly 40 years, U.S.’s policy has remained constant, and that is the imposition of sanctions against Iran for different reasons. The most complex method the U.S. uses against Iran is the so-called carrot-and-stick approach with an emphasis on the latter, the stick. However, Iran's reaction to sanctions has developed since previous decades and it is clear that a diversified, developing strategy will overcome a single, constant one.

U.S. policymakers have become disappointed with their plan for crippling the Iranian economy, because they have been unable to change Iran's security policy and at the same time Iran’s self-reliance has been reinforced. This point may be seen reflected in the words of Suzanne Maloney, the Vice President and Director of the Foreign Policy Program at the Brookings Institution:

The prospect of crippling the Iranian economy is a fallacy… The key prerequisites for a successful sanctions-centric approach - protracted duration and broad adherence - are almost certainly unattainable in this case. As a result, the recent embrace of sanctions by many in Washington represents a dangerous illusion.[1]

In addition, Ivan Eland, the author of a book in which he is skeptical about sanctions, wrote in the Washington Times, “If anything, the sanctions are likely to increase support for the regime as Iranians, like other people in similar circumstances of external pressure, rally around their flag.”[2]A policy of economic coercion, dubbed “maximum pressure,” is being implemented by means of targeted economic sanctions. Although they do not seem to have worked, their scope and depth are significant. First, we will discuss the intensity of economic sanctions against Iran. Next, we will look at the situation of the Iranian economy and how it is continuing.

Since the Islamic Republic of Iran was founded, all sorts of sanctions have been imposed. After taking control of the US embassy or “spy nest” in Tehran in 1979, the United States froze the Iranian government’s assets in the United States and in overseas US banks. This was a total of $12 billion according to the US treasury. That freeze of Iranian assets was later expanded to a full trade embargo.[3]

In 1992, the US Congress passed the Iran-Iraq Arms Nonproliferation Act of 1992. It declared that, “It is US policy to oppose any transfer of goods or technology to Iraq or Iran whenever there is reason to believe that such transfer could contribute to that country’s acquisition of chemical, biological, nuclear, or advanced conventional weapons.”[4] Then the Senate and House of Representatives passed the Iran and Libya Sanctions Act (ILSA) of 1996, which was later known as the Iran Sanctions Act (ISA) to extend the US sanctions’ legislation to cover domestic as well as foreign companies in order to reduce Iran’s ability to export oil and gas.[5] According to this act, investing in Iran’s petroleum industry was prohibited.

By looking at the history of sanctions against Iran, one can understand that there have been two major phases: before and after 2006, with greater intensity after 2006. Until 2006, the US sanctions against the Iranian economy were unilateral. But after 2006, the Security Council played an active role in the story of sanctions. In March 2007, the UN Security Council unanimously adopted Resolution 1747. This intensified the previous sanctions package while adding the names of some officials as targets of the sanctions and including more sanctions against Iranian financial institutions. In March 2008, the Security Council passed Resolution 1803 to reaffirm and uphold previous sanctions.[6] Resolution 1803 was passed in March 2008 expanding sanctions to include nuclear-related sanctions on Iran. In June 2009, the UN Security Council adopted Resolution 1929. This Resolution banned Iran from carrying out tests of nuclear-capable ballistic missiles, and imposed an embargo on the transfer of major weapon systems to Iran. After that, the US Congress passed the Comprehensive Iran Sanctions, Accountability, and Divestment Act (CISADA), which was related to investment in the Iranian energy sector. One of the most important sanctions against the Iranian economy was passed in January 2012. The European Union agreed to ban imports of Iranian oil which led to the reduction of Iran’s oil income. On the 14th of July in 2015, the United States, United Kingdom, France, Russia, China, and Germany signed the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA). After signing this, the US and the EU only issued waivers on some specific nuclear-related sanctions. In December 2016, the US Congress passed a ten-year extension of the Iran Sanctions Act (ISA).[7] On the 8th of May in 2018, Trump announced that he was withdrawing the United States from the JCPOA. He signed a presidential memorandum to introduce the "highest level" of economic sanctions against Iran.

As can be seen, the unprecedented economic pressure on the Iranian economy continued after the JCPOA. Donald Trump announced in May 2018 that the United States was indeed leaving the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) and the U.S. reimposed unilateral and secondary sanctions on Iran. The first wave of sanctions on August 6, 2018, targeted automobiles, foreign currency, and gold. The second wave, which went into effect on November 5, 2018, was more punitive and was aimed at Iran’s oil exports and its banks.[8]

The history of economic sanctions against Iran shows that the sanctions have targeted Iran’s energy sector, banking and finance, shipping and cargo inspections, ballistic missiles, nuclear and dual-use technologies, military equipment, and some other goods. Despite the broad scope of sanctions, the Iranian economy has been able to handle the pressure from the sanctions in such a way that the country has maintained a per capita income of USD 16,463. This puts Iran into the category of an Upper Middle Income Nation.[9]

Since the start of international sanctions, Iran’s GDP has increased. The Iranian government has benefited from high oil prices in compensation for the effect of the sanctions. However, this was not the same after 2012 when the oil-targeted sanctions were imposed.[10] In recent years, despite the maximum pressure campaign, the Iranian economy has returned to a modest growth in 2020 according to the data of the World Bank. As reflected in Table 1, it was anticipated that the growth rate would reach close to 0.9 percent in March 2021.[11] This shows that the Iranian economy can keep coping with sanctions. The Islamic Republic has an old playbook for circumventing such difficulties and maintaining its economy.

Table 1. Economic Indicators

|

Indicators |

1398 (3/21/2019 to 3/20/2020) |

1399 (3/21/2020 to 3/20/2021) |

1400 (3/21/2021 to 3/20/2022) |

|

GDP growth (real in Rials) |

–5.5% |

+0.2% |

+0.9% |

|

GDP (nominal in US $ at median exchange rate) |

$486 b |

$495 b |

$515 b |

|

GDP per capita (nominal) |

$5,927 |

$5,963 |

$6,123 |

|

Inflation |

37.0% |

31.0% |

29.0% |

|

Unemployment |

10.8% |

11.5% |

11.0% |

Source: https://www.worldbank.org

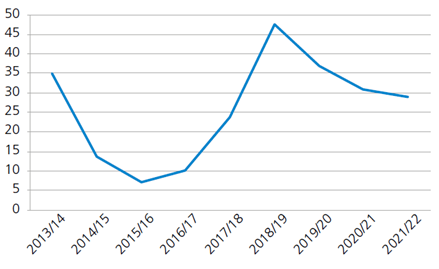

According to Figure 1, the inflation rate in Iran has grown dramatically after the JCPOA. But after the US’s withdrawal and its imposition of new sanctions (its maximum pressure policy), the trend has reversed.

|

Figure 1.Inflation Rate |

Source: https://www.worldbank.org

A disturbance in currency is another problem that has been caused by the sanctions for Iranian international trade. In return, Iran and its trading partners are using their own currencies in bilateral trade and settling any imbalances at the end of a specified period with a non-dollar currency. Furthermore, using a system of bartering with major partners, including China and Russia, is another method being used for circumventing sanctions.

Iran’s oil and gas sectors have been the main targets of the US sanctions in the various waves of sanctions. A dramatic reduction in oil exports was experienced after multilateral sanctions in 2012 and after the reimposition of sanctions by the Trump administration. In response to the sanctions, Tehran tried to give incentives to the importers of its oil and gas. Iran discounted the price of crude oil and offered practically free shipping in some cases.[12] Thanks to the sanctions, Iran is using its own tankers and insurance for shipping oil. Also, some oil importers are implementing and benefiting from oil-for-goods trade.

In addition, sanctions have given domestic manufacturers confidence that they can thrive. Adopting an “economy of resistance” in the face of sanctions, the government banned the import of many goods including home appliances, clothes, leather, and some foodstuffs. Due to the imposition of sanctions, Iranians are beginning to welcome locally produced goods. The fall of the value of the Rial following sanctions made exports very profitable. Iranians’ welcoming of domestic products and the profitability of exports have boosted Iranian manufacturing.

One important sector is the home appliance industry. The latest data released in this regard indicates that the manufacturing of refrigerators and freezers has risen 30 percent during the first ten months of this last Iranian calendar year (March 20, 2020 – January 19, 2021), as compared to the same period of time the previous year. At the same time, the production of washing machines and TV sets has experienced a growth of 53 percent and 44 percent respectively. Keyvan Gardan, the Director of the Electrical and Metals Industries and Home Appliances Office of the Industry, Mining, and Trade Ministry, has said that the manufacture of home appliances will hit a record high in the current Iranian calendar year (ending on March 20). He said that according to the plans and efforts made, despite the continuation of sanctions and the coronavirus pandemic, the previous record for home appliance production since the victory of the Islamic Revolution (1979) will be broken this year.[13]

Iran has also accomplished major strides in terms of medicine. Since the Iranian Revolution in 1979, the country has made it a priority to start the production of locally produced medicines and drugs. Prior to the Revolution, Iran relied on imports from foreign countries for approximately 70-80% of its pharmaceutical ingredients. As of 2018, it was estimated that around 97% of their medicines were produced and manufactured inside the country. Focusing on internal production boosted Iran’s economy making the country a major competitor in the world market. It also increased the country’s GDP due to the export of their domestically produced pharmaceuticals.[14]

As we can see over four decades, the Iranian economy has shown a great ability to circumvent tough sanctions. Myriad techniques have been developed by Iran in order for them to survive economically. The story of sanctions against Iran is a clear lesson for those countries who are dealing with or are prone to face sanctions from the so-called world-powers such as the US. Sanctions do not benefit the US anymore. Rather, they are to the benefit of the targeted nations. Iran's forty years of experience attests to this fact that, at least from one point of view, sanctions have indeed empowered Iran in many industrial and economic areas.

Due to the fact that the “maximum pressure” approach has been unsuccessful and ineffective, US authorities have shifted to plan B, which is negotiations. When sanctions are not effective, negotiations are used as an enticement for them to achieve their objectives. But a significant question exists. In the case of them being unsuccessful with plan B, do they have any other plan besides using sanctions and deals? The attack on the Natanz nuclear facility shows their plan C, and that is sabotage.

[1] Suzanne Maloney (2010), Sanctioning Iran: If Only It Were So Simple, Center for Strategic and International Studies.

[2] https://www.washingtontimes.com/news/2012/jan/17/iran-sanctions-wont-work/

[3] https://edition.cnn.com/2012/01/23/world/meast/iran-sanctions-facts/index.html

[4] https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/new-atlanticist/a-brief-history-of-sanctions-on-iran/

[5] Mahtab Alam Rizvi (2012), Tougher US Sanctions against Iran: Global Reactions and Implications, The Institute for Defense Studies and Analyses, New Delhi.

[6] https://archive.globalpolicy.org/security-council/index-of-countries-on-the-security-council-agenda/iran.html

[7] https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/new-atlanticist/a-brief-history-of-sanctions-on-iran/

[8] https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/in-depth-research-reports/issue-brief/how-iran-will-cope-with-us-sanctions/

[9] https://www.mordorintelligence.com/industry-reports/analysis-of-retail-sector-in-iran

[10] Mahdieh Aghazadeh (2014), International sanctions and their impact on Iran's economy, International Journal of Economics and Finance Studies, vol. 6, no. 2.

[11] https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/iran/publication/economic-update-april-2019

[12] Turak, Natasha, India may not be able to stop Iranian oil imports, despite the demands of U.S. sanctions, CNBC, September 7, 2018.

[13] https://www.tehrantimes.com/news/459089/Industrial-growth-achieved-despite-sanctions-pandemic

[14] https://borgenproject.org/medical-advancements-in-iran/