Education is one of the necessary measures for growth and development in every society. When studying educational advances, factors including the expansion of educational resources, plans to increase the means for education, the educational system’s share of the public budget, society’s literacy rate, school dropout rates, facilities and services, and educational plans are mainly taken into consideration. When we speak about the Islamic Republic’s achievements in different areas, promoting women’s literacy is undoubtedly one of the most significant features to address. By taking the above-mentioned factors into account, we can have a better understanding of women’s literacy and education, and this is a noteworthy area for study in developing a correct understanding of the status of women’s literacy and education. This examination of the aforementioned factors from before the revolution and up until today has focused on official figures released before and after the Islamic Revolution.

But it is necessary to examine the Islamic Republic of Iran’s general outlook on women before reviewing the performance of the Islamic Republic in terms of women’s literacy. Article 20 of the Constitution of the Islamic Republic of Iran clearly stresses human beings regardless of gender. It highlights human being’s equality in human, political, economic, social and cultural rights. Moreover, Article 21 specifically highlights the need to protect women’s rights by proclaiming that everyone should respect women’s rights. It states that the protection of these rights is one of the responsibilities of the administration and the governmental organizations of the country.

Another fundamental document that addresses women’s rights in Iran is the “The Charter of Women’s Rights and Responsibilities,” which was drawn up and ratified by one of the most important decision-making organizations in Iran, namely the Supreme Council of the Cultural Revolution. In the section on “education,” the document speaks of the following rights:

- Women’s right to benefit from good health (such as health in the working environment, etc.), information and the necessary means for education

- Women’s right to participate in politics, legislation, management, and the implementation of and supervision over health and treatment, specifically that of women

- Women’s right to have access to public education and to benefit from educational betterment and various means of education

- Women’s right to benefit from higher education to the highest level

- Women’s right to acquire skills and expertise – both in numbers and in quality – at the highest levels

- Women’s right to benefit from educational privileges in underprivileged areas

- Women’s right to undertake responsibilities in preparing school materials and other educational materials

- Women’s right as well as responsibility to take on positions which are befitting of their status and role in schools and other educational institutions

In addition to the fundamental policies and documents regarding women’s education in Iran, the leaders and high-ranking officials of the Islamic Republic of Iran have always stressed in their speeches the necessity to provide the necessary infrastructures and opportunities for the growth and development of women in their individual lives and in social life. For instance, the current Leader of the Islamic Revolution, Imam Khamenei, has stated:

Women play a role in social, political, scientific and economic activities. From the viewpoint of Islam, the field for women’s scientific, economic and political activities is completely open. If someone tries to deprive women from doing scientific work and economic, political and social endeavors on the basis of some supposedly Islamic viewpoint, they have acted against the divine decree. Women can participate in different activities as much as their physical ability and needs allow. They can engage in economic, political and social activities as much as they can. The holy Islamic law is not against this. Of course, because women are more delicate in terms of physical strength, they have certain restrictions.[1]

This special attention to women – specifically regarding their scientific and academic life – has led to tangible, noteworthy changes in the growth of their individual, social and scientific lives in post-revolutionary Iran.

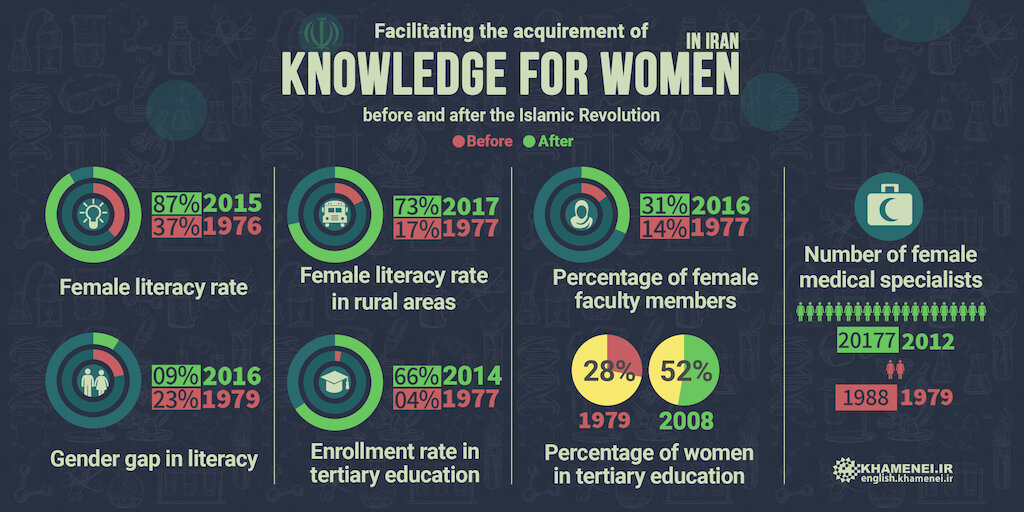

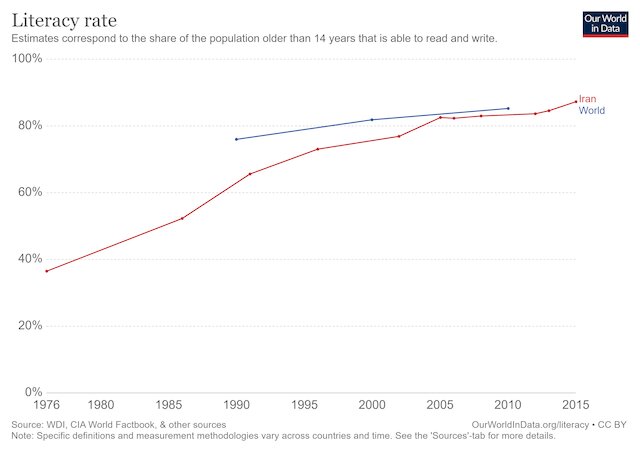

From the start of the Islamic Revolution in 1979, good measures were quickly adopted with determination in order to promote women’s literacy in a comprehensive, thorough manner. This bore tangible results. The rate of women’s literacy improved from 37 percent in the year 1976 to 87 percent in the year 2015. It is noteworthy that the rate of Iranian women’s literacy is even higher than that of the global average.

In addition to significant improvements in the rate of women’s literacy, after the Islamic Revolution, women have been in a far better condition - in terms of educational justice in the area of expanding literacy – in comparison with before the Revolution. Before the Islamic Revolution, the rate of female literacy was 24 percent, almost half the rate of male literacy, which was about 48 percent. However, after the Islamic Revolution, this gap in adult literacy rates dropped to 9 percent.[2]

When analyzing the period of the Pahlavi regimes, it is often claimed that women’s circumstances underwent many positive changes thanks to the modernization of society at that time. However, there is evidence that such changes were more superficial than practical. Abbasi and Musavi point out that not only did that modernization of Iranian society not bring changes generally speaking to the social condition of women in pre-revolutionary Iran, but it also “created division among a large number of women. It also undermined the position of a majority of women who had religious orientations in terms of educational and social awareness. This originated from the government’s indifference to the political and civil rights of women and from the government pushing women toward corruption. An example of this is their attempt to bring progress by forcing women to remove their hijab and subsequently their suppression of traditional women in order to enforce this."[3]

Specifically, in the area of education, certain changes stemming from modernization during the Pahlavi regimes have been disparaged as being inefficient due to their contradictions and striking differences with Iranian culture and identity. For instance, in his article “Education during the reign of the Pahlavi Dynasty in Iran (1941-1979),” Hamdhaidari argues that the new educational structures during the time of Mohammad Reza Pahlavi were “imposed” and that “they were totally irrelevant to the cultural, social and economic realities of the Iranian society and to the needs of society.” [4]

Moreover, the macro-policies of the regime in terms of the Iranian culture were oriented toward eliminating women from economic and social activities and defining them as a sexual commodity to be at the service of the patriarchal society. As more proof of the inefficiency of Pahlavi policies for improving the status of women and the female identity, Oriana Fallaci’s famous interview with Mohammad Reza Pahlavi wherein he responded to a question about empowering women clearly shows the humiliating, degrading outlook of Pahlavi rulers toward women. This leaves no room for doubt as to what they thought about women:

You [women] have never produced a Michelangelo or a Bach. You’ve never even produced a great cook. And don’t talk of opportunities. Are you joking? Have you lacked the opportunity to give history a great cook? You have produced nothing great, nothing![5]

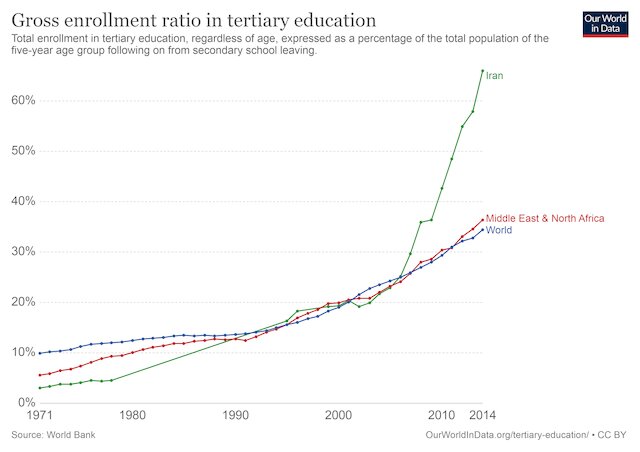

An examination of statistics can shed light on the differences between the outlook of former regimes in Iran and the Islamic Republic in the area of women’s involvement in science and research. On the basis of international statistics that compare the former regime with the Islamic Republic of Iran, the rate of women gaining admission to higher education has grown significantly in the post-revolutionary era. Specifically, female admissions into universities in the year 2008 exceeded 50 percent of the overall admission rate, reaching a total of 53 percent.[6] Iran's attempts to reduce the gender gap in higher education have been so effective that the World Bank declared in its annual report on developments in the Middle East and North African that, "In the year 2002 in Iran and for the fourth year in a row, the percentage of women passing the rigorous university entrance exam exceeded the percentage of men passing it." [7]

During the time of the Islamic Republic, women have found the opportunity to exponentially grow in all levels of higher education whereas such opportunities were absent in former regimes. Basically, the monarchical system in Iran adopted a shallow outlook toward women and looked at them as being commodities in society.

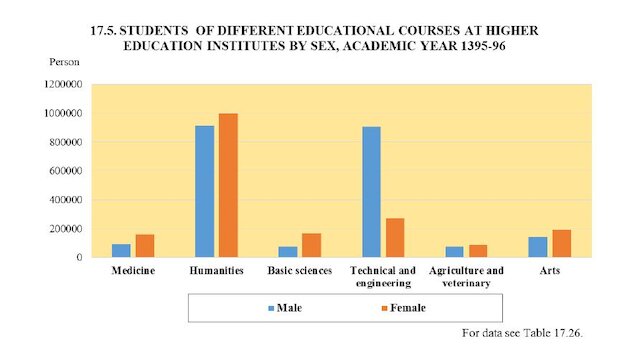

In addition to increased access to academic and scientific environments, women’s situation significantly improved in terms of the diversity of the academic fields available to them. Women have achieved relative equality with men in different fields of study and have even overtaken them in certain fields. As is clear in the following diagram for the year 2017, the number of female graduates in medical sciences and basic sciences exceeded that of male graduates. Only in technical and engineering fields has the number of male graduates been significantly higher than female graduates, a matter that is largely due to the nature of these fields.[8]

Irrespective of gender, access to universities and academic environments and interest in a higher education has significantly increased among Iranians after the Islamic Revolution compared to the pre-revolutionary era. In 1976, less than four percent of the Iranians who finished high school pursued higher education. But after the Islamic Revolution, in order to bring educational justice and with the necessary infrastructures becoming available, pursuing higher education became possible for a high percentage of the Iranian population. According to international statistics, almost 66 percent of those who finished high school entered universities in 2014. It is noteworthy to mention that Iran’s rate of success in expanding and providing academic and research facilities as well as encouraging its citizens to acquire literacy is almost two times higher than the global growth rate.

The rate of Iranian women’s literacy not only witnessed a growth in terms of quantity, but it has also enjoyed better geographical diversity and a fairer geographical distribution after the Islamic Revolution. In 1977, only 17 percent of the female population in rural areas were literate. But in 2017, 73 percent of the women in rural areas had become literate. This shows more than a 4-fold increase.[9]

The structural and intellectual reforms brought about in Iran regarding women led to the above-mentioned changes in women’s literacy rates. Allowing women to gain science and knowledge, facilitating their access to academic environments and strengthening the identity and dignity of Iranian women remarkably improved Iran’s condition in the area of public services and the development of expertise and skilled work. This is evidenced by a 10-time increase in the number of women physicians between the years 1979 and 2012. Before the Revolution, the number of female physicians was 1,988. But that figure reached an astonishing 20,177 after the Revolution.[10]

In the case of management in educational centers, women’s roles in these centers after the Revolution is incomparable to that of the pre-revolutionary era. Women’s increased access to higher education has made it possible for many more women to take on managerial posts in the field of education and has led to an increase in the number of female professors and faculty members in universities. In its report on the number of female faculty members in universities, the World Bank stated that the number of female board members has witnessed a 3-time increase, growing from 11 percent in 1970 to more than 30 percent in 2016.[11]

[1] http://farsi.khamenei.ir/speech-content?id=2812

[2] https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SE.ADT.LITR.FE.ZS?end=2016&locations=IR&start=1976&view=chart

https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SE.ADT.LITR.MA.ZS?locations=IR

[3] Somaye, Abbasi, and Musavi Mansoor. “The Status of Iranian Women during the Pahlavi Regime (from 1921 to 1953).” Women's Studies, vol. 5, no. 9, 2014, pp. 59–82.

[4] Hamdhaidari, Shokrollah. “Education during the Reign of the Pahlavi Dynasty in Iran (1941–1979).” Teaching in Higher Education, vol. 13, no. 1, 2008, pp. 17–28.

[5] https://newrepublic.com/article/92745/shah-iran-mohammad-reza-pahlevi-oriana-fallaci

[6] https://knoema.com/atlas/Iran/topics/Education/Tertiary-Education/Female-students-in-tertiary-education

[7] Gender and Development in the Middle East and North Africa: Women in the Public Sphere. World Bank, 2004.

[8] Iran Statistical Yearbook 2016-2017. Statistical Center of Iran, 2017.

[9] Iran Statistical Yearbook 2016-2017. Statistical Center of Iran, 2017.

[10] Simforoosh N, Ziaee SAM, Tabatabai SH. “Growth Trends in Medical Specialists Education in Iran. 1979 – 2013." Arch Iran Med. 2014; 17(11): 771 – 775.

[11] https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SE.TER.TCHR.FE.ZS?locations=IR

Comments